In the best tradition of brecht, a RPG can comment itself.

In his paper ”The Self-Reflexive Tabletop Role-Playing Game”, Evan Torner studies three different tabletop role-playing games and the ways they reflect upon themselves as games, highlighting the mechanisms of a role-playing game through the mechanisms of play.

Self-reflexivity is the quality of an artwork drawing attention to its own nature as a fiction. The classic example is the Verfremdungseffekt (“alienation effect”) in Bertolt Brecht’s plays, where a play’s action would be interrupted by song commentary or the sets would be made to look explicitly like theatre sets instead of believable backgrounds. Another example Torner supplies is David Mitchell’s novel Cloud Atlas, whose structure highlights the impact and outcome of literary texts in its narrative. A self-reflexive tabletop role-playing game, then, is one that in Torner’s words “expose[s] the machinery, while keeping it running”.

To define that machinery, Torner draws on a theory of game ontology that is a series of generalizations over categories of design choices in different games. These include “interface, rules, goals, entities, and entity manipulation”. Interface is things like the playing surface, dice, and players; goals are those player motivations that are encouraged by the game’s system and social circumstances, such as competition or storytelling; entities are “facts” established in the fiction such as – Torner’s example – Skeletor has the “Climb” skill. Entity manipulation is the exercise of agency and experimentation with these entities: Skeletor takes a penalty to climbing Snake Mountain in the rain.

Torner then explores the ways that three different games reveal the different ways in which they give rise to narratives or create meaning.

First up is Epidiah Ravachol’s role-playing game What Is a Roleplaying Game? It is a game about bank robbers whose perfect cover for their heist is that they are also astronauts scheduled to launch on the day of the robbery. The game rules are minimalist, designed to produce a series of increasingly absurd situations while also following the author’s argument about what role-playing games are. To play WIARPG is to face “role-playing theory in the raw” – as well as “a couple of hours of dumb fun”.

Meguey Baker’s storygame 1,001 Nights, based on the classic Arabian Nights story cycle where the Princess Scheherazade tells a story each night to the Sultan, ending in a cliffhanger to avoid being executed at dawn. The players take on the roles of storytellers in the court of the Sultan, and act out their personal wants through the simple tales that they relate, casting each other as characters in their tales.

Here, Torner refers to stance theory, an early theoretical formulation about player-character interaction that has directly or indirectly informed all three games explored in the article. The theory outlines four different stances that a player can assume regarding their character and the character’s motivations. In actor stance, players make the character’s decisions based only on knowledge that the character would have. In author stance, they make the decisions based on what they as a player want and then come up with a plausible motivation for the character. That motivation differentiates author stance from pawn stance, where the character is merely an extension of the player’s will. The pawn stance is often considered bad role-playing. The fourth, director stance, allows the player to decide not only their character’s motivations but also what happens to them, where, and how. In most cases, players assume actor or author stances. However, the nested narrative format of 1,001 Nights muddles the stances, validating the pawn stance, and highlights the nature of human interaction and player motivations.

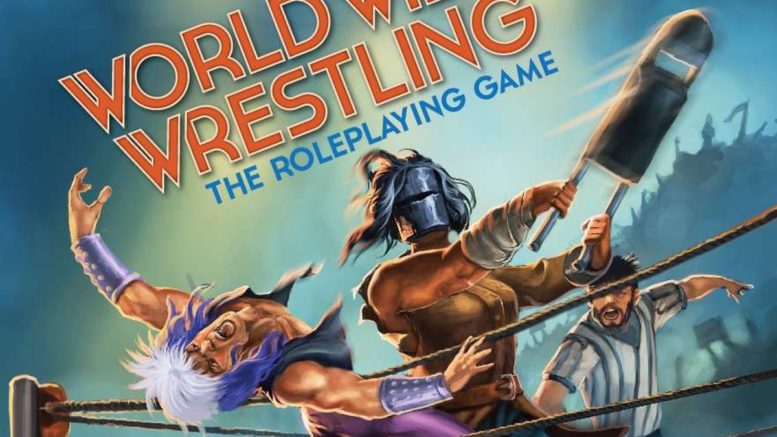

Third and last, Torner examines World Wide Wrestling by Nathan D. Paoletta, itself a game based on the Apocalypse World system. It is a game about professional wrestling, and the characters are wrestlers working for a franchise. The wrestlers in turn play their on-screen personas in t

he larger-than-life narrative of the wrestling show – who will in a given match be playing, say, Face or Heel, the good or bad guy, as the narrative requires. These nested layers of roles make visible the blurred lines of player and character motivation. The game’s self-reflexivity emphasizes how role-playing games are, to quote Daniel Mackay, “a new performing art”.

These three games are not the first self-reflexive role-playing games, but they all treat role-playing games seriously and emphasize the idea of collaboration, or “playing for togetherness”, allows role-playing games to examine their own workings with analytic precision.

Original paper: G|A|M|E, issue 5/2016, “The Self-Reflexive Tabletop Role-Playing Game” by Evan Torner.

Article plucked from: http://playlab.uta.fi/when-a-role-playing-game-looks-at-itself/

Be the first to comment on "When a Role-Playing Game Looks at Itself"